This afternoon, at Evensong for the eve of St Edmund’s Day, I was collated and installed as an Honorary Lay Canon of St Edmundsbury Cathedral. This is a personal appointment of the Bishop of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich and makes me a member of the cathedral’s College of Canons. It is a rather humbling honour to receive from the Cathedral of my home town, and it feels especially fitting that I have been assigned the stall named ‘Historiographers’. The appointment will last for three years, although it may be renewed for a total of six.

I am not by any means the first lay canon of St Edmundsbury Cathedral, and indeed the Cathedral’s best known lay canon was the late Ronald Blythe, who was installed in 2003. Indeed, Ronald Blythe bequeathed a Reader’s blue preaching scarf ornamented with the arms of the Diocese (a privilege of a canon) to the Cathedral, and I wore it today as I am also a Reader.

The Cathedrals Measure 1999 makes provision for the appointment of laypeople as canons of Church of England cathedrals, but lay canons have in fact existed since the Middle Ages. Originally, the term ‘lay canon’ was a synonym for ‘secular canon’; that is, non-resident secular priests who had the title of canon of a cathedral or collegiate church. However, the statutes of some orders of regular canons (such as the Gilbertines) also permitted laymen to be admitted to the order as canons; and of course women could become canonesses in various religious orders. Furthermore, by the 13th century it was not unknown for a layman to obtain appointment to a canonry in order to farm its income, while appointing a vicar or proctor to perform his canonical obligations. Elsewhere in Europe, noble lay canons (who were sometimes hereditary) sometimes underlined their status by wearing armour under their surplices in choir, and by carrying a hawk on one hand on certain important feasts.

As a cathedral foundation, St Edmundsbury Cathedral dates only to 1914, although the Church of St James that became the Cathedral was founded by Abbot Anselm in the 1120s in symbolic fulfilment of a vow to go on pilgrimage to Compostella. However, St James’ Church succeeded a previous church on the site (on the north side of the Abbey Church’s west front) dedicated to St Denis, which may have been served by a college of secular canons and was probably founded in the 1080s by Abbot Baldwin. The canons of St Edmundsbury Cathedral thus continue an ancient tradition of canons in Bury St Edmunds which can be traced back to the original community of secular priests and laypeople (‘canons’ might be an anachronism) who cared for the shrine and body of St Edmund before Benedictine monks replaced them in 1020. Furthermore, this was not the last secular college in Bury; in 1480 Jankyn Smyth founded the College of the Sweet Name of Jesus, which housed and supported the chantry priests and chaplains of both St Mary’s church and St James’s (although these were not canons). This college endured until its dissolution by Edward VI in 1547.

The Council of Trent did not outlaw lay canons, but it denied them the right to speak in chapter. Lay canons survived the Reformation in England, since a canonry did not carry with it a cure of souls, and it was not until 1661 that the law required all residentiary canons to be in priest’s orders. But even then, lay canons continued to be appointed as honorary members of cathedral chapters, and laymen could be presented to prebends. Dr Johnson’s dictionary defined lay canons as men ‘who have been, as a mark of honour, admitted into some chapters’. There are sporadic references to lay canons of various English cathedral chapters throughout the nineteenth century; Carlisle, for example, had four lay canons throughout this period. Installations of lay canons continued into the 20th century; in 1936, for example, Portsmouth Cathedral put in special stalls for its lay canons. However, the Cathedrals Measure 1999 revitalised the idea of lay canons, establishing them as part of the diocese’s College of Canons (which replaced the Greater Chapter). The College of Canons is distinct from the Cathedral Chapter that actually governs a cathedral, and is not part of its foundation, but it is the College of Canons which formally elects a new bishop for the diocese.

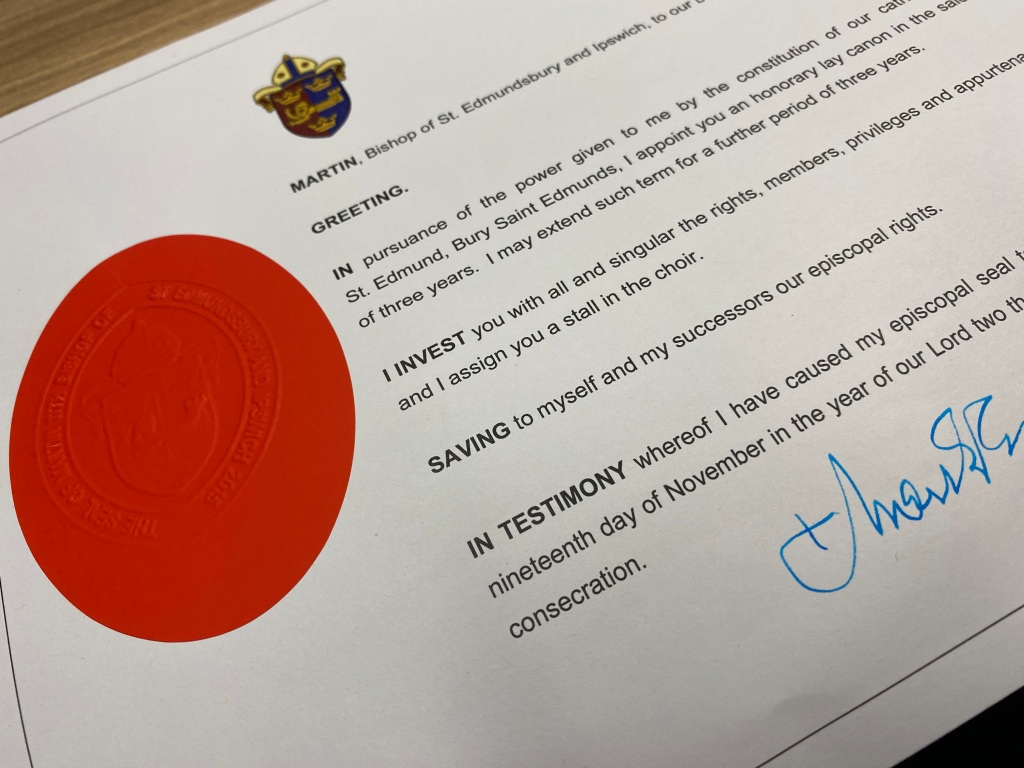

The installation of canons is a surprisingly complicated affair that begins behind closed doors, with the Diocesan Registrar administering the required oaths to the clergy and laypeople about to be installed as canons. For a lay canon, these are the Oath of Allegiance to the King, an oath of canonical obedience to the Bishop, and an oath to maintain the statutes and customs of the cathedral church. The new canon subscribes these oaths (by signing them) and is then presented with a deed of collation, to which the Bishop’s seal has been affixed.

In the service itself the new canons are introduced by the Bishop and Dean, and later in the service comes the collation, when the Dean formally presents the new canons to the Bishop; the Bishop then asks the Registrar to confirm that the canons have made the required oaths, and the Bishop then confirms the canons’ appointment and blesses them. Then the Bishop directs the Dean to install the canons, and the Dean leads them to the nave altar. Here, with their right hands on the Gospels, the canons swear (again) to observe the cathedral’s statutes and customs. Once this is done, the installation itself takes place when the Dean leads the new canons by hand into the quire to their assigned stalls. The canons remain standing until the Dean has read the formula of installation for each canon. The canon then sits in their stall and the installation is formally complete. One reason why the rite of installation is quite so convoluted is that canonries were once treated as items of property, and thus installation carries with it traces of the procedure of livery of seisin, whereby ownership of a freehold was passed on by a series of ritual actions.