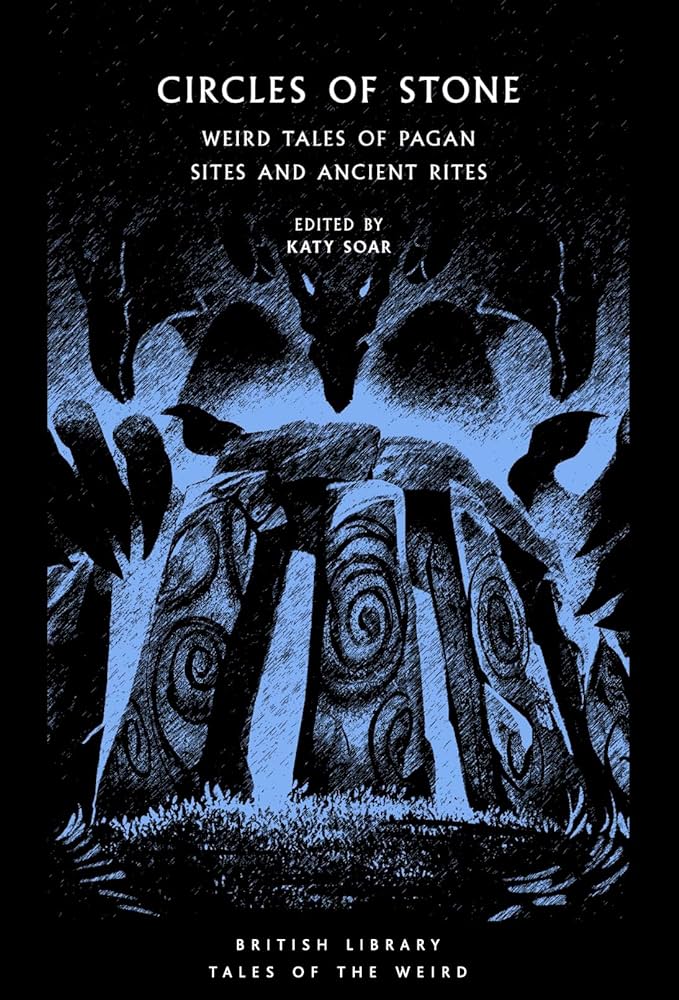

Katy Soar (ed.), Circles of Stone: Weird Tales of Pagan Sites and Ancient Rites (London: British Library Publishing, 2023), 238pp.

“Something clings to it, some curse, some abomination …”

“They held a subtle sense of majestic power, of latent evil; a sense of darkness and decay; a sense of age and forgotten secrets …”

Why are ancient standing stones so disquieting? Is it their extreme age that disturbs us, a reminder not only of the mortality of the individual but the mortality of whole civilisations and cultures? Or is it their mystery – the frustration of never having any certainty about what they were for, or what their builders intended? Do we dislike sharing a landscape we consider ‘ours’ with an indelible yet ultimately incomprehensible past? Or is it their isolation in the landscape – the unheimlichkeit of encountering human-made structures far from anywhere, with no obvious purpose – the disquiet of the detritus of ritual long forgotten? Or is it the stories that cling to these stones that disturb us, the folklore and the interpretations of generations of antiquaries (convinced these stones were saturated with the blood of sacrifices)? Or is it even the very appearance of the stones themselves that suggests the macabre – the Rollrights pockmarked by deep time, the vaguely anthropomorphic Whispering Knights, the portal-like Stonehenge, the sinister bulk of the vast stones of Avebury that famously featured in the title sequence of the unsettling TV series ‘Children of the Stones’?

All these factors, no doubt, feed into the impression of the eldritch that often attends prehistoric monuments in the British landscape. There can be no doubt that, in the modern world, these are liminal places – eagerly visited every year by many people with different motivations, but belonging resolutely to another world that lies always just beyond the horizon of our understanding. The 15 tales in this volume, dating from between 1893 and 2018, all approach the idea that megalithic monuments are somehow sinister or eldritch in their own distinctive ways – as well as finding different ways to somehow bridge the great gap in time between the megaliths and us. Katy Soar was the co-editor, with Amara Thornton, of an earlier collection, Strange Relics (Handheld Press, 2022), which I reviewed here. Whereas the focus of Strange Relics was classic stories of the archaeological supernatural, the focus of Circles of Stone is solely on tales featuring prehistoric standing stones and megaliths of some kind.

Human sacrifice, and its dark power resonating down the centuries, is a common theme of several of the stories. In both E. F. Benson’s ‘The Temple’ (1924) and Rosalie Muspratt’s ‘The Spirit of Stonehenge’ (1930), something about the stones themselves compels people to sacrifice by the shedding of blood – leading in both cases to a tragic suicide. In Muspratt’s story (writing as Jasper John), it is ‘elementals’ who are drawn to the evil perpetrated at Stonehenge in the form of human sacrifice and haunt the place, seeking to possess or influence people who come into contact with it (an ‘elemental’ also seems to be at the root of the poltergeist-like activity in Nigel Kneale’s ‘Minuke’ (1949), and perhaps also involved in ‘The Dark Land’ (1975) by Mary Williams). In Algernon Blackwood’s ‘The Tarn of Sacrifice’ (1921), however, it is not gods, demons or ghosts who bridge the gap between modernity and megaliths, but rather reincarnation – in a story heavily imbued with the aftermath of the First World War, which has turned the idyllic paganism of the Edwardian era to dark thoughts of blood sacrifice. Similarly, while the stories are set in various locations it is the West Country and Cornwall in particular that predominate – the British landscape dominated more than any other, perhaps, by the unsettling presence of the megalithic past.

In A. L. Rowse’s 1945 Cornish-set story ‘The Stone That Liked Company’, which to my mind is one of the most interesting of the collection, it is the megalith itself which is somehow the protagonist – the source of its own power, somehow, rather than a vehicle of supernatural beings:

There was something horrible in the threatening headlessness of the stone, the shapelessness that was yet suggestive of power, of a ruthless natural force imprisoned in it incapable of expressing itself, or of any release.

The longstone of the tale, which seems to move about by night, is filled with latent power, ‘the embodiment of grey despair, deserted for centuries by its votaries, living its own terrible secret life, the embodiment of imprisoned force.’ The idea of sentient or moving stones also recurs in ‘Where The Stones Grow’ (1980) by Lisa Tuttle, while in Elsa Wallace’s ‘The Suppell Stone’ (2018) the stone actually consumes people.

In H. R. Wakefield’s folk horror ‘The First Sheaf’ (1940), set in late Victorian Essex, the sacrificial megalith is a ‘pillar’ bearing an illegible inscription, and with some sort of dish in its top, that stands in a field left uncultivated by local people; and, although Wakefield does not say as much, the ‘pillar’ is implicitly a Roman altar – given the absence of megalithic sites in the east of England and the presence of writing and a patera (the integrated dish for sacrificial offerings at the top of a Roman altar). This makes for an interesting comparison with John Buchan’s novel Witch Wood (1927), where the altar at the centre of the folk horror action is similarly a much worn Roman one. The gods of Wakefield’s story are apparently real enough, however, since the invocation of the pagan ‘priest’ brings sudden thunder and lightning.

Stuart Strauss’s ‘The Shadow on the Moor’ (1928) is obviously an American story about the British countryside, as the author’s unfamiliarity with British archaeology and the use of certain terms (‘fall’ for autumn, and the assumption that a small community would have a mayor) suggests he may never have visited Britain. It is, nonetheless, an atmospheric story where it is the stones themselves who are somehow the protagonists: ‘As he now glanced at it he thought it seemed to have a personality – a soul old and evil – longing to crush to atoms the lives of those who entered its once sacred portals’. By contrast, in ‘Lisheen’ (1948) by Frederick Cowles the stone circle is almost incidental to the story, the site of the pagan worship of 17th-century Cornish villagers that is clearly inspired by Margaret Murray’s theory of the ‘witch-cult’. For once, however, Cowles’s story is not about human sacrifice, but rather about pagan rites and, ultimately, departure to an otherworld.

20th-century authors responding to Britain’s megalithic sites seem to have struggled with the paradox of the stones’ antiquity. At a time when the myth of human progress was at its zenith, it went without saying that the people of the past must have been ‘primitive’ – quasi-simian, even, given the prevailing racial ideas of the pre-War era. And yet the vast size and sophistication of the stones, together with their extraordinary longevity, makes them ipso facto evidence of a culture capable of extraordinary technological achievements. The idea that sophisticated people existed in the past, just as much as the thought that the seemingly ‘primitive’ cultures of colonised lands were nothing of the kind, was a discomforting one – and it was perhaps the contradiction inherent in primitive peoples achieving astounding architectural feats that suggested the idea of magic.

The centrality of the horror of human sacrifice to so many stories about Britain’s megalithic past reflects the archaeology of the time, where some element of human sacrifice was often assumed in the distant past – by analogy with what Roman authors tell us of the human sacrifices of the druids. In this sense, the association between megalithic sites and human sacrifice was a lingering relic of William Stukeley’s powerful and influential identification of megalithic sites as druidic temples. Interestingly, this theme seems to have become more common in the mid-20th century, and the two earliest stories in the collection, J. H. Pearce’s ‘The Man Who Could Talk With The Birds’ (1893) and Arthur Machen’s ‘The Ceremony’ (1897) are not concerned with human sacrifice. Perhaps this was because Frazerian ideas about folk customs as the remnants of rites of sacrifice went mainstream only in the 20th century.

We now know that stone circles and other megalithic monuments were not, in all probability, sites of human sacrifice; indeed, the evidence that human sacrifice existed in Neolithic and Bronze Age Britain is slight, and the practice of human sacrifice seems to have been an innovation of the Iron Age. There were, in all probability, no ‘altar stones’ associated with these sites, because if there were we would expect to find archaeological evidence of sacrificial activity. However, even if it was not associated with sacrifice, we do now know the extent to which a site like Stonehenge was associated with death; the entire surrounding landscape was peppered with burials. The association of megaliths with sacrifice is very much of its time, as is the evocation of ‘elementals’ – harking back as it does to the popular Spiritualism of the 20th century. We now know that the people who built the megaliths were not ‘primitive’, and have rightly jettisoned such a pejorative cultural concept. The long shadow cast by the druids is finally being dispelled.

How, then, does contemporary literature respond to Britain’s megalithic past, if archaeology is to inform imaginative responses to these monuments? This anthology offers a few hints. Perhaps the traditional tales told about these sites will become more important than their supposed ‘original purpose’, which often feels unrecoverable. Above all, however, the trajectory suggested by this anthology seems to be towards a focus on the stones themselves as quasi-sentient objects, pregnant with presence and meaning. The secret of their original purpose and meaning, held with such resolute determination, imbues them with a kind of cultural charge – batteries of the strange, simultaneously eternally familiar and implacably alien. This collection is one of the very best British Library Publishing has yet brought out in the Tales of the Weird Series.