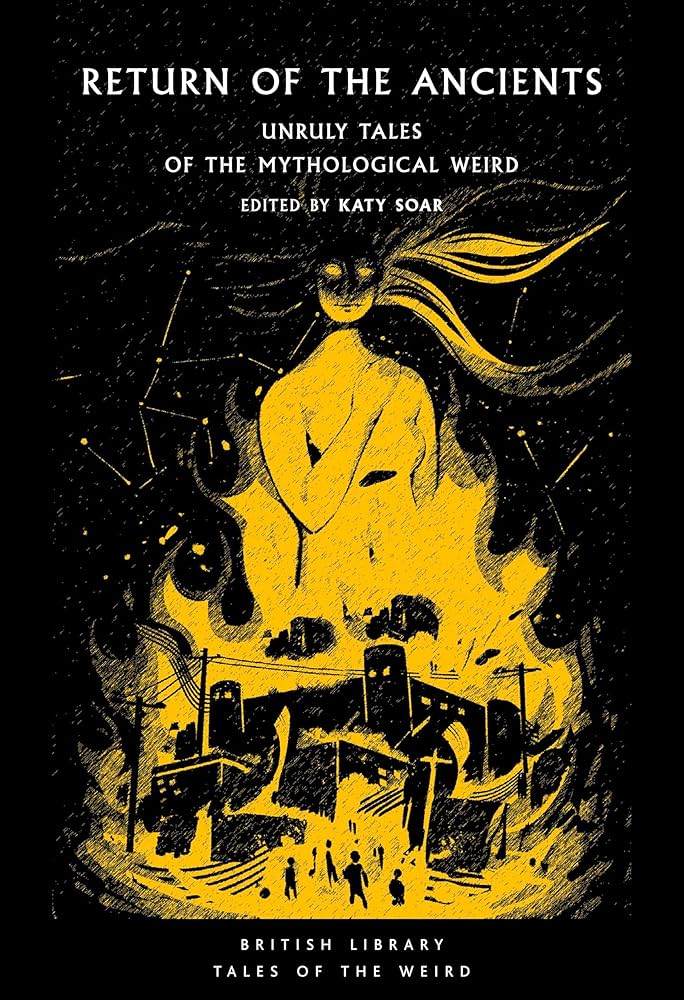

Katy Soar (ed.), Return of the Ancients: Unruly Tales of the Mythological Weird (British Library Publishing, 2025), 319pp.

“For months now I have resisted and I can resist no longer. I’m going to the grove tonight …”

Ghost stories, traditionally, are about the returning dead – but it is not just individual human beings who number among the dead. Entire cultures and civilisations die, and so do religions – and, along with them, their gods. And if the shades of human beings are capable of returning even after death, then what of the shades of dead gods? Gods derive their power, after all, from the attentions of their worshippers; once all those worshippers are dead and gone, the god is safely buried – until someone, somehow, is tempted or drawn to awaken, to refresh or to feed the forgotten deity. This sort of thing is the premise for a lot of modern cinematic horror, from The Exorcist to Ghostbusters; but it is rooted in an older literary tradition of weird literature focussed on the power of mythological figures breaking into the mundane world of the present. It is this ‘mythological weird’ that is the focus of Katy Soar’s latest collection of forgotten short stories for the British Library Tales of the Weird Series, Return of the Ancients, which follows on from her earlier collection in the same series Circles of Stone (2023, see my review here) as well as a collection of archaeologically-themed ghost stories she edited with Amara Thornton, Strange Relics (2022, see my review here).

Return of the Ancients consists of fourteen weird tales published between 1890 and 2008, where deities and mythological beings from cultures as diverse as Greece and Rome, Egypt, ancient Mexico, ancient Carthage, Celtic Britain and Viking Scandinavia break into and disrupt life in the modern world – usually because some unwise antiquary or collector has disturbed them. Crucially, these are mythological beings from real cultures – not, as in H. P. Lovecraft’s stories, gods from a mythos that is itself invented. A couple of the stories – Vernon Lee’s ‘Dionea’ and John Buchan’s ‘The Wind in the Portico’ – were already known to me, but most are unfamiliar. As Soar notes in the Introduction, the traditional literary ghost story often dwells on that which is out of place – the stories of M. R. James, famously, play on the contrast between an apparently cosy reality and the monsters and ghosts that break so alarmingly into it. Yet, as Soar asks in the Introduction, an undead god is the ultimate outsider, the ultimate other: ‘What can belong less in our contemporary times than the presence of a deity whose temple doors should have long since closed?’ This is especially true in a society where Christianity is taken as a cultural norm – which was still true of the late 19th- and early 20th-century societies that form the backdrops to most of these tales.

The first question many critics like to ask about supernatural stories is what they are really about – if the stories do not arise from the actual fear that former deities might return, then what fears and anxieties motivated them? And for what fears and anxieties does the return to life of dead gods serve as a metaphor or representation? I am not sure we should dismiss too hastily the possibility that a genuine fear of the return of obsolete deities does exist – and I shall return to that later. But clearly the recrudescence of dead gods is an idea with significant metaphorical power. It provides a language for anxiety about the decline of Christianity and the rise of secularism – a worry that was not confined, in the 19th and 20th centuries, to people of faith. Christianity still has the power to hold some mythological terrors at bay in several of these stories – but, like the crumbling ‘frog wall’ of Carl Jacobi’s ‘The Face in the Wind’ (1936) it is a crumbling edifice barely holding back the resurgence of ancient terrors. For many people in the period, secularism – and especially the more decadent manifestations of secular culture – was equated with ‘paganism’, a word that was used quite freely to denote any perceived breakdown of accepted Christian mores. In particular, ‘pagan’ was a word repeatedly used to describe an attitude to sexuality that contrasted with society’s official mores, and sexuality looms large in these stories – from the intoxicating reincarnated goddesses of ‘Dionea’ and ‘Above Ker-Is’ to the monstrous-yet-beautiful harpies of ‘The Face in the Wind’ and the seductive yet terrible Tiamat of ‘Serpent Princess’. So far, so normal for early 20th century weird fiction; the return of old gods could serve as a metaphor for social and moral change as well as for the decline of Christianity and faith in the Christian God.

Colonialism gave rise to further anxieties about the capacity of western Christian culture to hold in check forever the powerful creeds and cults of ‘savage’ peoples – an orientalising discourse more than hinted at in stories in this collection (‘Pussy’ (1931) by Flavia Richardson, ‘The Veil of Tanit’ (1932) by Eugene de Rezske, ‘Serpent Princess’ (1948) by Edmond Hamilton and ‘The Owl’ (1931) by F. A. M. Webster) that draw on imagined visions of the civilisations of ancient Egypt, Carthage, Mesopotamia and Mexico. Just as colonised peoples clung stubbornly to their old gods in the real world, so authors of weird fiction were much preoccupied with the notion that atavistic cults had somehow survived in the colonising West itself, and survival (along with various forms of reincarnation and supernatural re-instantiation) is one of the key ‘mechanisms’ by which old gods manage to return in this collection. This is to be expected – it reflects the methodological and theoretical assumptions of anthropologists, ethnographers and folklorists in the period, and its appeal in fiction is obvious.

‘Survivals of the old faith among the old people’ play a key role in my favourite story in this collection, R. Ellis Roberts’s ‘The Great Mother’ (1923), which shows a strong influence from Arthur Machen. Here, we are tantalised with the idea that cults of old gods already exist among people in rural Oxfordshire, into which unwary Oxford undergraduates might be drawn – and Roberts is at pains to point out that such ‘genuine’ survivals bear no relationship to the paganising affectations of undergraduate aesthetes. Interestingly, such notions were not confined to fiction – as I explored in my book A History of Anglican Exorcism, the young Gilbert Shaw sincerely believed he encountered pagan cults in Evesham and in the Lincolnshire countryside on missions in the 1920s. The pagan survivals are less subtly rendered in ‘Justice Tresilian in the Tower’ (1980) where Ken Alden cobbles together every scrap of mythology associated with the Tower of London to evoke an imagined Middle Ages riddled with underground paganism, and in ‘Family History’ (1998) where a Mithraic cult survives on modern Hadrian’s Wall.

The idea of pagan survival is one that has lingered a lot longer in popular imagination and in fiction than it has in scholarship – perhaps because the idea of lingering paganism is seductive and narratively appealing (injecting a bit of colour into an otherwise monochromely Christian religious landscape); but perhaps also because the idea that paganism is somehow still alive beneath the surface of an outwardly Christian and secular post-Christian culture provides a satisfying explanation for the failure of either Christianity or secularism to prevail in 20th-century Britain. If we are somehow still pagans at heart, if the old gods are not quite as dead and buried as they seem, then that might explain an aching spiritual void in many people that neither respectable Christianity nor materialistic pleasures can fill. And here, perhaps, is the most disturbing horror of all – not just that terrible heathen gods may return and break into the modern world, but that at some level people unwittingly want them to come back. And as the old, once cherished religious structures (yet long since despised and reviled by right-thinking people) begin to crumble away irrevocably, perhaps there the slightest twinge of awareness that they provided spiritual protection as well as a self-righteous institution to kick against. Because humans are spiritual beings: in the end, their spiritual needs must be met, and if the seemingly worn-out creed of Christianity is done away with, that rejection is not without spiritual consequences. Something else will fill the void, and it won’t simply be materialism. Perhaps the old gods are just waiting for their moment.

Leave a comment