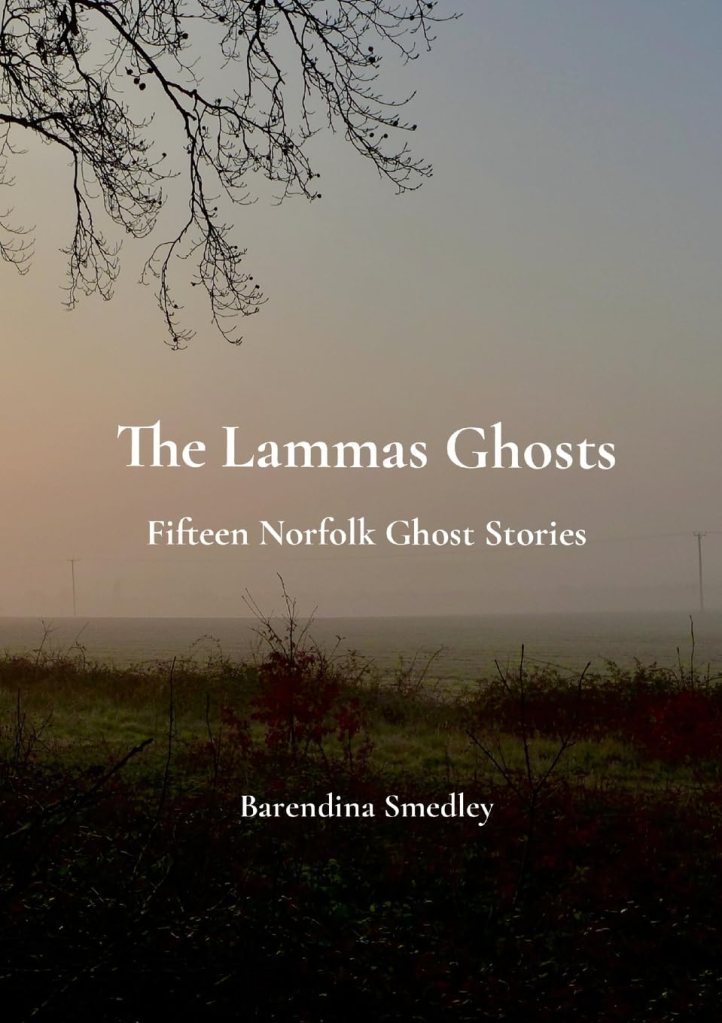

Barendina Smedley, The Lammas Ghosts: Fifteen Norfolk Ghost Stories (privately published, 2024), 208pp.

… an aching longing for what is lost, what has been broken purposelessly, what has been taken before its time but yet still has enough life left in it to make its absence known, felt, acknowledged.

Although critics often speak of the ‘antiquarian ghost story’ as a subgenre of supernatural fiction invented by M. R. James, it would perhaps be truer to say that the ghost story is antiquarian literature’s dark twin – or its misbegotten yet undeniable sibling. As it is in Barendina Smedley’s story ‘Flesh on the Bones’, where even speaking of an evil Norman nobleman wreaks havoc on a modern Norfolk village, antiquarian research often uncovers the unpleasant and the unsettling. And even if it doesn’t, it can leave the antiquarian with a lingering sense that something more underlies a story, and that there is an experience and an atmosphere to be recovered that is just beyond the horizon of what even the most detailed research can capture. Indeed, in some early antiquarian research this yearning to make sense of the eldritch intimations awoken by engagement with the past is to the fore; Thomas Browne’s maudlin yet profound Hydrotaphia is perhaps the best known example, but Henry Spelman was preoccupied with the macabre consequences of sacrilege, Elias Ashmole practised magic as well as antiquarianism, and John Aubrey was never able to shake the feeling that the antiquarian is in some sense a necromancer. But as the heavy hand of the Enlightenment fell on antiquarianism, it ceased to be acceptable for antiquarians to have much to say about the emotional, psychological and (dare I say it) supernatural epiphenomena of the strange business of spending one’s life with the dead.

The antiquarian ghost story is, perhaps, the unquiet spectre that eventually burst forth from that attempt at repression. There is only so much detached and ‘scientific’ investigation of the deep past that a human being can manage before the accumulated weight of loss and grief, the heaviness of our mingled solidarity with people of the past and our utter alienation from them, breaks in upon our calm and erudite studies. This is why I hold the somewhat controversial view that the antiquarian ghost story is not, in fact, a genre that any writer can attempt – trying as best they can to mimic the Jamesian style and setting. There isn’t a ‘vibe’ that can simply be captured by a sufficiently talented writer. No: the antiquarian ghost story, properly speaking, is a ghost story written by an antiquary, by which I mean a sincere lover of and seeker after the past, the sort of person who always has one foot outside the present. Good antiquarian ghost stories emerge from an author’s unsettling experience of dwelling with and delving deeply into the tangled roots of the past. Because the difference between try-hard Jamesian pastiche and the authentic modern antiquarian ghost story seems to me quite obvious, and few collections fall into the latter category. Barendina Smedley’s The Lammas Ghosts, however, is one of them.

I knew I wanted to read this collection because I had already encountered the title story on the author’s website and was struck by its depth, subtlety, and compelling pacing. The other fourteen stories in the book do not disappoint, either, and I am delighted that Barendina Smedley has decided to gather her writing together in this form. In the tradition of James (but very far indeed from being a pastiche of Monty), these stories are intensely local, and rooted in a very specific landscape of the Norfolk coast. They emerge from, and are informed by, long experience and deep knowledge of a place, of the kind that lends meaning even to subtly evoked uncanny experiences – for if you know everything about a place, even a slight deviation from the norm is unsettling. These are stories of measured pace, whose protagonists are usually thoughtful and observant students of their surroundings; yet they are also very varied, ranging from contemporary to early modern settings and featuring unexpected supernatural phenomena, from traditional ghosts to disturbing apparitions of the future, as well as unclassifiable beings like ‘Old Tom’. Likewise, the tone of the stories varies from the comforting ghosts of ‘A Very Kind House’ to the sharp, discordant horror of ‘The Visitor’ – with everything in between.

There are, however, overarching themes of the collection beyond just the unifying location and landscape. These are stories preoccupied with the theme of buildings and houses, as deeply architectural in their inspiration as James’s stories were archaeological and codicological in theirs. Perhaps better than anything I have ever read, they evoke what it is like to live in an old house, and the character and personality of old houses. These stories explore the potential of the mysterious, partitioned yet never quite fully understood spaces of houses built by people with ideas of living very different from our own, yet also eerily like us. It is perhaps this deep empathy with old houses that enables the author to place some of the stories convincingly in historical settings – something which I know from experience (having attempted and then abandoned numerous such stories) is very difficult without falling prey to a sort of clichéd pantomime of the past. But ‘Old Tom’, told from a child’s perspective (also very challenging) and set in the reign of James I, is one of my favourite stories in the collection.

Another overarching theme of the collection is the accumulated weight of loss, which somehow breaks into the present in the form of the supernatural. In one way, this is a common theme of all collections of ghost stories. But what I appreciated about this collection is that the overwhelming emotion that pervades them is not fear, but sadness – indeed, some of them are genuinely moving. If there is fear, it is usually because characters have purposely cut themselves off from the capacity to accept that the memories that permeate a house or a landscape demand some sort of acknowledgement, some sort of co-existence – like the people in ‘The Old Road’ who build an awful modern house over an ancient road, and are robbed of sleep by ‘the sharp cries of mourners hanging in the air’. Several of these stories read as warnings against shutting out the past by the performance of modernity – because the past will always find a way to enter (in one story, ‘Incomers’, even finding its way into a teenager’s computer game). Like all the best ghost stories, those in The Lammas Ghosts are as much about the present as they are about the past. But they are honest about the present – honest about admitting that the present is always unavoidably haunted by the past.

Leave a comment