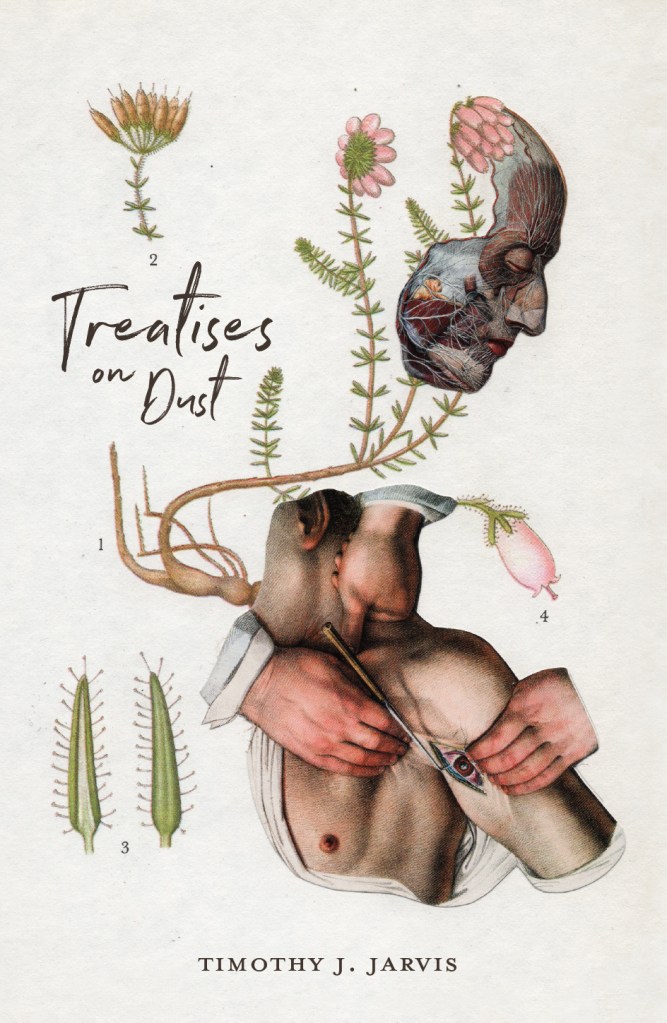

Timothy J. Jarvis, Treatises on Dust (Dublin: Swan River Press, 2023), 239pp.

It has been a long time since I have read a work of fiction so compelling that I not only wanted to keep returning to it, but also lost all desire to do anything other than read it. At the risk of cliché, I can honestly say that Timothy Jarvis’s Treatises on Dust was a book I devoured, while not wanting it to come to an end. I was initially drawn to it by the promise that it echoed and paid tribute to Arthur Machen, a writer I love; so accordingly I ordered the book from Swan River Press – but I was busy on the day it was delivered, and so (like one of the characters in the book itself, in fact), I left the brown paper package that contained it unwrapped on a shelf. I then forgot about it until, a few days ago, the niggling thought that I’d ordered a book of short stories I hadn’t yet read materialised at the back of my mind. So I rummaged through my bookshelves, found the unopened package and finally tore it open to read Treatises on Dust.

Treatises on Dust is perhaps the most Machenesque modern book I have read. Jarvis continues Machen’s project of ‘the interweaving of the numinous and the mundane’, as the Hermit of Barnsbury puts it in ‘A Chance Encounter in Barnsbury’. This means adherence, in the main, to contemporary settings; and the settings are often urban, or suburban. The surface mundanity (and modernity) is the point, and it only accentuates the breaking in of other levels of reality when this does occur. The stories in the book – at least, most of them are stories, others are very short pieces more like prose poems – bristle with mysterious found books and messages, spontaneous atavistic rituals, and characters teetering at the edge of sanity; they challenge the line between dream and reality, and between symbol and actuality, becoming something like the talismanic art of Austin Osman Spare – ostensibly works of creative fiction, but perhaps in reality something more akin to seeings, even evocations.

Jarvis pays tribute to Machen in many large and small ways. He makes several uses of the device of a narration – or multiple narrations – within the story, at which Machen excelled; bookshops and obscure books (in one case, Machen’s own The House of Souls) often play a key role in the story, and even Machen’s evil, primordial fairies receive some attention. Machen’s famous ‘Londonising’, his delight in finding the strange in the mundanity of the city simply by wandering its streets, is resurrected here – but extended to the suburban landscape of the Home Counties. Jarvis combines three apparently unrelated stories into a literary portmanteau, ‘Three Relics’, in a knowing nod to the structure of Machen’s The Three Impostors.

But Treatises on Dust is very far from being a mere pastiche of Machen, or a Machen fanfic. Jarvis, the modern Machen, has his own distinctive preoccupations; a kind of atavistic animism lurks close to the surface in the recurring significance of animal anatomy and the lush descriptions of plant life. There are also hints of folk horror that go beyond anything Machen envisioned. And Jarvis is not, it seems, interested in the same aspects of Machen that fascinate me – as a historian, it is Machen’s obsession with Roman Britain and with the ancient past that speaks to me most deeply. There is nothing wrong with that, of course – the different facets of truly great writers are large enough in themselves to stimulate legacies of their own.

In fact, in spite of the presiding presence of Machen, Treatises on Dust stands out for its originality and truthfulness. There are no explanations for the weird things that happen, no hints of an alternative cosmology lying behind the high strangeness. That would be too easy; it is more mysterious than that. This is neither high nor low fantasy; it is not world-building, but reality-unveiling. The book may be Machenesque, but it is not an attempt to interpret Machen for a modern audience but an effort to capture the clarity of vision – indeed, quite literally the clairvoyance – of Machen’s most compelling works, which seemed to hint at an awareness of a truth beyond apparent reality that sometimes manifests itself via the most mundane situations. I did not relate as well to some stories as to others, but overall Jarvis achieved a feat I thought well-nigh impossible for a contemporary writer. He managed to convince me that his fiction emerges not from mere skill or artifice, nor even from creative inspiration, but from a truthful perception of realities beyond the mundane. In short, the book sent my pineal gland tingling.

Leave a comment