Rosemary Pardoe (ed.), The Ghosts & Scholars Book of Follies and Grottoes (Sarob Press, 2022), 177pp.

Rosemary Pardoe, the doyenne of the Jamesian ghost story, has edited several compilations of supernatural tales for Sarob Press – all in the vein of the stories published in the magazine Ghosts & Scholars that she edited for so many years – if not actually consisting of stories culled, in a thematic fashion, from its pages. Of the thirteen stories featured in the Book of Follies and Grottoes, eight have previously appeared in Ghosts & Scholars (a magazine where one of my own ghost stories has previously been published, in fact). Each one of the stories in this volume is built around a folly or grotto that in some way evokes, provokes or restrains the preternatural.

Reading the collection caused me to reflect on what it is that makes follies of various kinds so creepy – for creepy they certainly are. One of the best-known ghost stories to feature a folly – or, rather, a garden feature – is M. R. James’s ‘Mr Humphreys and His Inheritance’, and the folly story can perhaps be classified as a subset of stories about garden hauntings. For if the decaying haunted house is a terrifying prospect, the overgrown haunted garden is arguably more fearful still – combining as it does the exuberant life of encroaching, choking, heedless nature with the prospect of an encounter with the dead. Yet within the haunted garden the folly occupies a special place, for follies are inherently unnatural: buildings without any normal, useful purpose that embody the unchecked will of their capricious designers and builders.

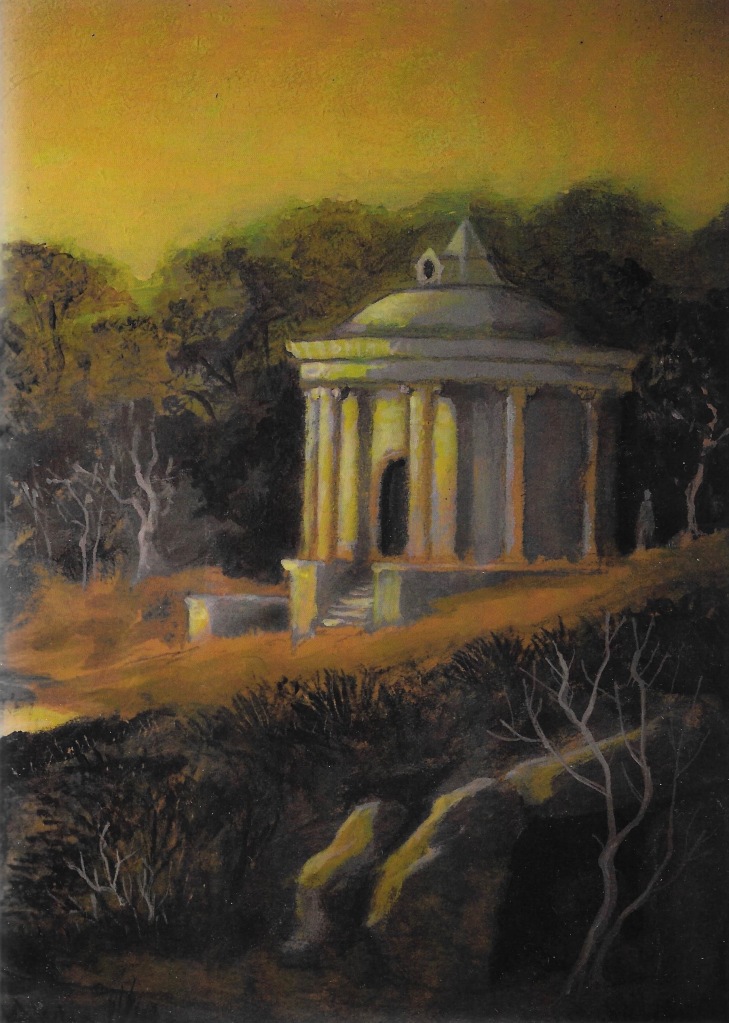

The first reason follies are creepy, therefore, is their lack of a normal domestic purpose. Unlike other ancillary buildings found on an estate, a folly exists only to be viewed as part of a picturesque vista, and perhaps visited as some sort of summerhouse (or, like several of the follies in these stories, as a viewing platform). Furthermore, some follies were created to be ruined; and thus decay was integrated into their design from the very beginning. A folly’s state of general decay is a feature, not a bug; and a folly is thus a kind of undead building – a structure brought into being only to exist in a kind of half-life of intentional decay.

Another reason why follies are creepy is their association with pagan religion. Many roofed garden structures in the gardens of England’s great houses are known as ‘temples’, and based loosely on ancient buildings such as the Tower of the Winds in Athens, although in most cases the name ‘temple’ simply describes their Neoclassical architectural style rather than any sacred use for which these glorified summerhouses were intended. But there were notable exceptions, such as Sir Francis Dashwood’s antics at West Wycombe when he dedicated a temple to Bacchus; and the existence of societies such as the Hellfire Club fuelled a lingering suspicion that some of the bien pensant Enlightenment connoisseurs of England were so immersed in the Classical world they loved that they had not only abandoned Christianity, but had also begun to quietly embrace paganism. In light of this fear of creeping apostasy, which was occasionally articulated by the more thoroughgoing churchmen of the time, the ‘temples’ of England’s estates take on a certain dark glamour, as potential sites of abominable rites in honour of long dead deities, breathing life back into dark powers dormant since antiquity. And the idea that a philopagan squire brought something more than sculptures back from the Grand Tour lies at the heart of several of the stories in Rosemary Pardoe’s collection. In this respect, folly stories can be located in that subgenre of supernatural tale (with longstanding antecedents in English folklore) about the evil squire.

But temples were not the only buildings on which follies and other garden structures were modelled. Some were inspired by mausolea, and it is this link between follies and mausolea that gives them another creepy association: with death and burial. I am not aware of any actual follies that really were mausolea – they would not, after all, have been built on consecrated ground – but many English country estates have a church and therefore a churchyard close to or right next to the main house, meaning that the sometimes grandiose mausolea of the dead are sometimes adjacent to (if not part of) the garden. Furthermore, as the demands of eighteenth-century landscaping led to the clearance and relocation of village communities too close to a great house, the ancient churches of country estates were often left marooned in the garden – little more than follies themselves, one might say, especially if they came to be rebuilt in a fashionable style. Follies in ghost stories sometimes turn out to be unholy mausolea – dwelling-places of the unsanctified dead, like a replacement for the estate churches whose crypts really did house the genteel dead. The world of the folly is thus the world of the necropolis, the house of the dead that stands as a counterpart to the house of the living at the heart of the estate.

Folly stories seem to be dominated disproportionately by the presence of one historical period: the eighteenth century, as the era most strongly associated with the construction of pointless buildings in artificial landscapes. It was an era of vast injustice and obscene disparities of wealth, now seemingly neatly packaged for the genteel visitor to country houses and estates. The folly story is perhaps an epiphenomenon of a deep-seated unease with the period – an era of great beauty and astounding aesthetic accomplishment that was underpinned, in many cases, by profound evil and exploitation. Here as elsewhere the ghost story provides a kind of cultural escape valve for our unease, in the stereotype of the evil Georgian connoisseur whose apostasy and spiritual abominations unleashes dark forces: a revelation, on one interpretation, of the true ugliness of the eighteenth century. But perhaps this is an interpretation too far; however interpreted, the subgenre of ghost story that concerns itself with follies, grottoes and other useless buildings is handsomely represented in Rosemary Pardoe’s collection, which will be enjoyed by lovers of antiquarian ghost stories for years to come.

Leave a comment