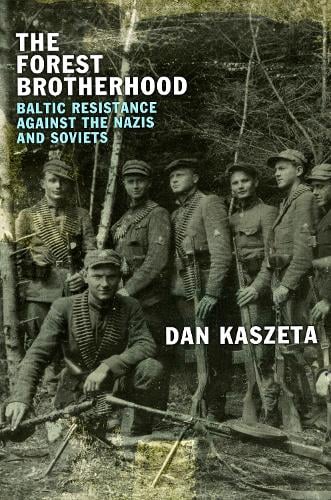

Dan Kaszeta, The Forest Brotherhood: Baltic Resistance Against the Nazis and Soviets (Hurst and Co., 2023), 272pp.

In the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania the Second World War did not come to an end in May 1945. Occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940, then by the Nazis in 1941, and then again by the Soviets between 1944 and 1990 under a protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, for the Baltic states the nightmare of tyranny simply went on and on. But central to the story of the 20th-century suffering of these nations is the resistance mounted by the ‘Forest Brothers’, partisans who resisted these occupations and, long after the guns had fallen silent elsewhere in Europe, continued to fight a guerrilla war against the Soviets into the 1950s. But the pro-independence Baltic partisans have routinely been characterised, by those focussed on the Soviet side of the story, as fringe nationalists at best and Nazi collaborators at worst. The aim of Dan Kaszeta’s Forest Brotherhood is not only to tell the story of these remarkable men and women, but also to set the record straight regarding their politics, and their allegiance.

The emergence of the Baltic republics of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia as independent sovereign nations from the wreckage of the Russian Empire at the end of the First World War was little short of a miracle; German defeat and Russian revolution and civil war created the space for these nations to re-emerge onto the world stage; but, as Kaszeta shows, their democratic political culture was still in its infancy – and not altogether healthy – when the USSR struck in 1940. Yet these were also nations with long histories of struggle and resistance to maintain their culture and identity in the face of imperialist aggression. The first Soviet occupation was brief but devastating, with huge swathes of the political class and intelligentsia deported to Siberia. The arrival of the Nazis created a brief mirage of relief, as if the Germans might treat the Estonians and Balts better than the Soviets had; and there were some in the Baltic states who actively collaborated with the Holocaust, and SS legions were raised in both Latvia and Estonia (the Lithuanians, it should be noted, successfully boycotted such efforts). But it soon became clear that the Nazis were no more sympathetic than the Soviets to the idea of Baltic independence, and it was when the Soviets returned in 1944 that the partisan resistance as we know it began in earnest, with former members of the armed forces of the Baltic republics, along with a motley band of schoolteachers and men evading conscription to the Red Army (as well as a few far-right fanatics, it must be said) taking refuge in the forests to continue a long, slow war against the Red Army and the NKVD.

The partisans hoped – even expected – that sooner or later there would be a ‘hot’ war between the USSR and USA; and they expected relief from the Americans, which of course never came. They took pains to identify themselves as the provisional armed forces of states that, under international law, still existed (and whose incorporation into the Soviet Union was never recognised by the USA), dressing where they could in old uniforms of the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian armies. It was a resistance without hope of military or strategic success; in the early days the partisans mounted heroic acts of defiance worthy of the Baltic crusades, such as when Albina Neifaltienė defended Miškakalnis Hill against the NKVD in May 1945 with a machine gun, killing over 400 Soviet troops before the partisans were overwhelmed. But, as Kaszeta shows, the partisans gradually drew back from such ‘set piece’ confrontations with the Soviets, hunkering down in the forest to engage in a long, slow-burning campaign of sabotage and assassination against the occupiers. It was this strategy that allowed the partisans to endure as long as they did, although without supplies or support from the West it was impossible for the partisans to survive forever. The ammunition they captured from the Soviets no longer matched the World War Two-era weapons many of the partisans carried, or vice versa, and the environmental conditions of the forest took their toll. More and more partisans were captured, or quietly slid back into civilian life in order to continue the resistance by other means.

Armed resistance in Lithuania is traditionally said to have come to an end with the capture of the legendary leader Vanagas (‘Hawk’) in 1956, but some partisans stayed in hiding for much longer. The last armed Latvian partisan, Arnolds Spārns, was captured in 1959 but survived and lived into the 2010s, while the last Estonian forest brother, August Sabe, was tracked down by the KGB while fishing in 1978, and drowned after a final battle with the Soviets. In Lithuania, a partisan named Stasys Guiga (‘Tarzanas’) went to ground after the rest of his group was destroyed in 1952 and remained in hiding until his death by pneumonia in 1986, having hidden at a remote farm near Vilnius for decades.

Why did the Forest Brothers continue a fight for so long that could not be won? The fight against the might of the USSR was not one that could be won militarily, clearly. But there was a propaganda war to be won, too, and there seems little doubt that the partisans did win it. As Kaszeta shows, time and time again the partisans prioritised the printing of samizdat literature over any other kind of operation, to the point that the Forest Brothers (and sisters) were sometimes more like armed printers than guerrillas. Legendary acts of daring and heroism were propaganda in and of themselves, regardless of the actual damage they inflicted on the Soviet machine, and when those partisans who had evaded capture drifted back to the towns and cities they fomented a social and intellectual resistance that had been kept alive by tales from the forest. Like the pre-War Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian diplomats who clung on throughout the world in embassies of dubious diplomatic status, just by surviving for as long as they did the Forest Brothers kept the idea of Baltic independence alive. And in that they succeeded.

Dan Kaszeta’s book is undoubtedly the most comprehensive and detailed account of the Baltic partisan resistance movement in English, but it is far more than just political hagiography or a litany of legends. Kaszeta is concerned with the reality and dynamics of partisan warfare, and he does not shy away from difficult historical questions and the political complexity of the partisan movement. He also captures the diversity of the political and military cultures of the three Baltic nations, who underwent the same struggle in the years 1940-1990 but are very different from one another. The Forest Brotherhood is history-writing at its best: astute, nuanced, politically relevant and deeply researched.

Leave a comment